Association of Diabetes and Tuberculosis in the Department of Internal Medicine at the CNHU-HKM of Cotonou from 2010 to 2019: Review of the Literature

Author(s): Azon Kouanou Angèle1*, Agbodande Kouessi Anthelme1, Akogbeto Kpessou Dieu-Donné1, Missiho Mahoutin Semassa Ghislain1, Wanvoegbe Armand Finagnon1, Sokadjo Yves Morel2, Dovonou Comlan Albert1, Assogba Houénoudé Mickaël Arnaud1, Falade Adélakoun Ange Géoffroy1, Oba Richard1, Aïdasso Jean-Christ1, Zannou Djimon Marcel1, and Houngbe Fabien1

1Department of Internal Medicine of CNHU-HKM Cotonou, Benin.

2National Reference Center for Research and Management of HIV infection, Benin.

*Correspondence:

Azon Kouanou Angèle, Department of Internal Medicine and Medical Oncology of CNHU-HKM Cotonou Benin, Phone: 97997850/95711618.

Received: 19 August 2021 Accepted: 15 September 2021

Citation: Angèle AK, Anthelme AK, Dieu-Donné AK, et al. Association of Diabetes and Tuberculosis in the Department of Internal Medicine at the CNHU-HKM of Cotonou from 2010 to 2019: Review of the Literature. Diabetes Complications. 2021; 5(3); 1-5.

Abstract

Introduction: Tuberculosis is now a major public health problem worldwide and is one of the top 10 causes of death in the world. It can be associated with diabetes. According to the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 16-46% of people infected with TB suffer from diabetes. In Benin, work on this association is partial. The objective of this study was to investigate the association between diabetes and tuberculosis in a hospital setting.

Methods. This was a descriptive and analytical cross-sectional study with a retrospective collection conducted in the Internal Medicine Department of the CNHU-HKM of Cotonou over a 10-year period. All hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients with diabetes and tuberculosis were included, regardless of the type and location of tuberculosis.

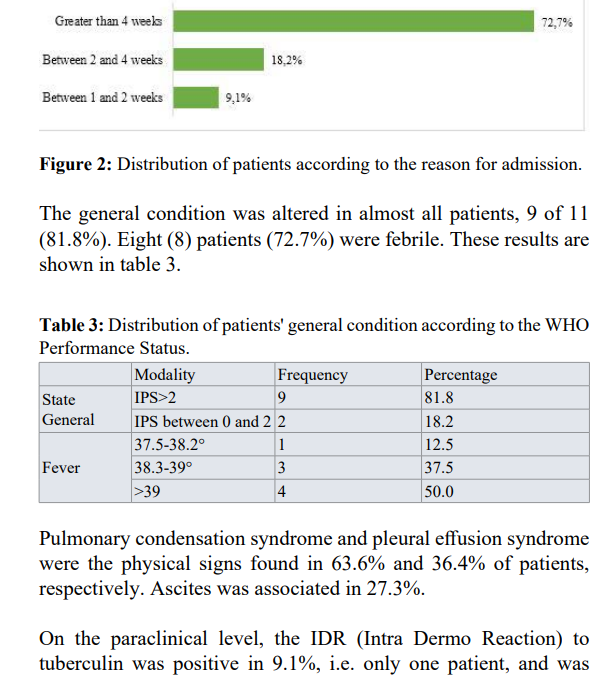

Results. Among the 273 patients hospitalized during the study period, 11 cases of diabetes-tuberculosis associations were found, representing a hospital frequency of 4.1%. The sex ratio was 0.8. The mean age was 48.6 + 6 years with extremes of 30 and 70 years. Diabetes preceded tuberculosis in 100% of cases. Chronic cough and dyspnea were the reasons for management in 72.7% and 45.5% of cases. Diabetes was type 2 in 81.8%. Sixty-three point six percent (63.6%) of patients had poor glycemic control. Eighty-one point eight percent (81.8%) of patients had pulmonary involvement. Patients were treated with antidiabetic and antitubercular drugs. The evolution was favorable in 72.7%. Twenty- even-point three percent (27.3%) died.

Conclusion: The association of diabetes and tuberculosis was 4.1% in the department. It is usually a type 2 diabetes, poorly balanced. The location was pulmonary in 9 out of 11 patients.

Keywords

Introduction

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Koch's bacillus). Today, it is a major public health problem worldwide and is one of the 10 leading causes of death in the world [1] with 10 million cases estimated in 2018 by the WHO and 1.2 million deaths [2]. Despite the abundance of scientific publications and control actions implemented for several decades, tuberculosis (TB) remains a growing global scourge with 7.3 million cases in 1996, 8.8 million in 2002, and 10 million in 2019 [2-4].

Since 1980, the emergence of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) pandemic has led to a significant increase in TB incidence and mortality in many countries, particularly in Africa [5]. Indeed, more than 25% of TB deaths occur in the African region where TB is classically associated with poverty, promiscuity, and malnutrition [1]. Tuberculosis occurs in 80% of cases in its pulmonary form, but can affect other organs such as lymph nodes, kidneys, intestines, meninges, and sometimes even the urogenital system [2].

In Benin, the number of people infected with TB increased by 12% between 2017 and 2018 to 4000 cases. In 2019, over 6500 referenced cases, 920 deaths were recorded, that is (14.15%). The incidence of the disease is estimated in 2019 to be 55 cases per 100,000 inhabitants [2-4].

According to the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (IUATLD), 16-46% of people infected with tuberculosis have diabetes and the convergence of these two diseases is likely to be a major public health crisis6. Diabetes is a metabolic disease characterized by chronic hyperglycemia related to a defect in insulin secretion and/or action [7]. This increasingly common condition was worldwide in 2012 at the base of 1.5 million people to which 2.2 million deaths caused by diabetes- related complications are added and making a total of 3.7 million deaths [8].

According to a study from the University of Texas, diabetic patients infected with tuberculosis not only have a difficult recovery, but they also had a higher risk of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) [9]. The prevalence of diabetes in patients with TB was 39% in Texas and 36% in Mexico [10].

In Africa, the frequency of tuberculosis in diabetic patients remains high at 4-15% [11]. In Benin, research on this association is partial. Given the importance of this association and the increase in its frequency and sometimes its radiological and therapeutic specificities, and given the irregularity of the data in Benin, we are proposing to identify the particularities of this association with the aim of evaluating the association between tuberculosis and diabetes in the Internal Medicine Department of the CNHU-HKM of Cotonou.

Methods

We conducted a descriptive and analytical cross-sectional study with a retrospective collection, spread over a period of 10 years from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2019. This study was conducted in the Internal Medicine Department of the Centre National Hospitalier et Universitaire Hubert Koutoukou Maga (CNHU-HKM) in Cotonou, Benin. It included all patients admitted, hospitalized, and treated in the department and in whom the association between tuberculosis and diabetes was retained. All patients with a history of diabetes confirmed by a physician and whether or not they were under treatment, or any patient with two fasting blood glucose levels above 1.26 g/l during hospitalization, were considered diabetic. Classification as type 1 or 2 was done according to WHO criteria. Tuberculosis was considered if the patient had a positive bacilloscopy on direct sputum examination or if there was clinical evidence associated with suggestive radiological images.

Inclusion criteria

Patients hospitalized in the department, regardless of sex and age, for diabetes with a diagnosis of tuberculosis, or patients hospitalized for tuberculosis with known or newly diagnosed diabetes were included.

Exclusion criteria

Patients whose diagnosis of tuberculosis was rejected after initiation of treatment and patients with incomplete or illegible medical records were excluded.

The variables studied were: sociodemographic variables (age, sex), clinical data (functional signs, general signs, physical signs, history, type of tuberculosis, immunosuppressive terrain, duration of apyrexia, outcome of treatment), therapeutic data (therapeutic regimen, tolerance, compliance with treatment.) Duration of hospitalization), paraclinical variables (microbiology, bacteriology, hematology, blood glucose, imaging).

Data collection was done using a survey form. Data entry and analysis were done using R software (version 4.0.0) with a significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

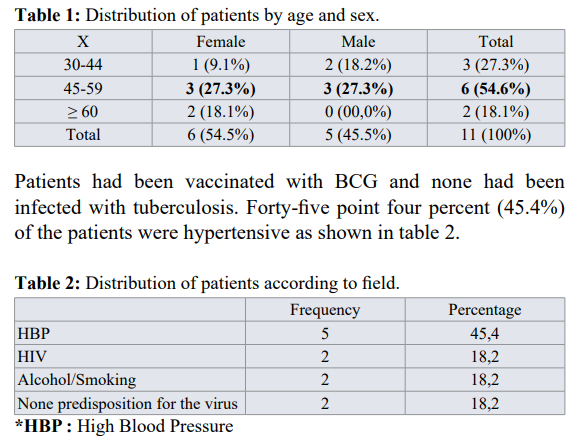

Over 3758 patients hospitalized in the department during the period, there were 267 cases of tuberculosis, i.e. a frequency of 7.1%. Over 267 patients diagnosed with tuberculosis, 11 had diabetes. The frequency of the association between diabetes and tuberculosis was 4.1%. The mean age was 48.6 + 6 years with extremes of 30 and 70 years. The sex ratio was 0.8 in favor of women. Table 1 presents the different results obtained.

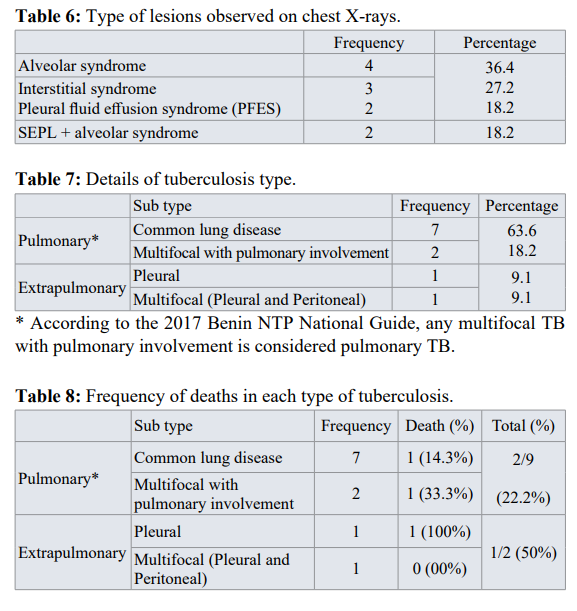

Regarding to imaging, patients had performed chest radiography. Table 6 shows the different results obtained. For the type of tuberculosis, pulmonary tuberculosis accounted for 81.8% and extrapulmonary tuberculosis (pleural, peritoneal) 18.2% in diabetic patients. The details are shown in table 7.

During the hospitalization, patients were put on insulin depending on the case, whatever the type of diabetes. Tuberculosis was treated with the anti-tuberculosis drug ERHZ (Ethambutol, Rifampicin, Isoniazid Pyrazinamide). The dosage given, was according to the weight of each patient. The duration of hospitalization varied from 3 days to 31 days with a favorable evolution in 72.7% of patients. The average duration of apyrexia was 2 days, the extremities being 1 day and 12 days. There was a high case fatality rate of 27.3%. Sixty-six point seven percent of the deceased cases were pulmonary tuberculosis cases. See table 8 for details.

Discussion

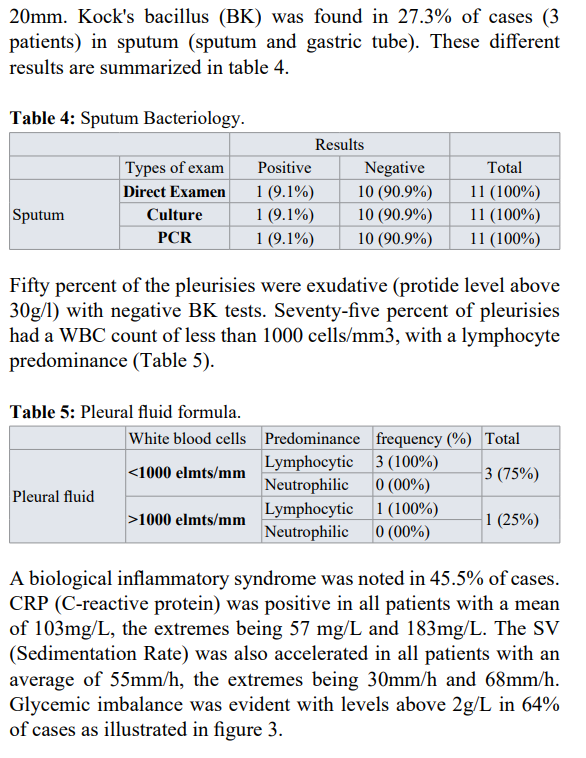

The prevalence of the association between diabetes and pulmonary tuberculosis was 4.1% in our study. This rate is higher than that found in Europe by Aubertin et al: 1% [12] and in Tunisia by Chabbou et al: 2.31% [13], but it is lower than those found by Mugusi et al in Tanzania and Frances Lester et al in Ethiopia respectively: 5.4%, 6.1% [14,15]. The mean age of the patients was 48.6±6 years, more or less the same as that obtained in Tunisia: 42 years [13], and in Algeria: 50 years [16]. The sex ratio was 0.8. This result is identical to that of Morad et al. [17] but contrary to the results of Balde et al in Guinea [18] and Diarra et al. in Bamako [19]. These results could be explained by the difference in the study population. The study population was small in our case (11 patients). BCG vaccination does not seem to be a guarantee of protection in the study, although Frances Lester et al. [14] consider that all diabetics with a negative TST should be vaccinated, the risk of contamination remains high in diabetics because of their immunocompromised condition [13]. All patients (100%) were already known to be diabetic before the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis, as has been reported in the literature [12,15,16,20]. Tuberculosis infection is certainly the cause of diabetes imbalance. In our study, the frequency of association of tuberculosis and diabetes was 4.1%, a result close to that of other studies such as Balde [18], Diarra [19], Morad [17] who found respectively 3.35%; 5.7%, 5.8%. In our patients, 18.2% had an HIV infection, thus raising the problem of morbid associations and the opportunistic nature of certain infections. We did not find any notion of tuberculosis infection in any of the patients. Diarra et al. [19] had reported 36.7%. Our patients were smokers and alcoholics in 18.2% of cases. Tobacco and alcohol are both factors that can depress immunity and constitute an additional factor to diabetes. This rate is lower than that of Diarra [19]: 23.3%. Type 2 diabetes accounted for 81.8% in our series. These data are in agreement with the literature [8], confirming the findings of other studies [21-23]. The clinical picture is characterized by the presence of a fasting blood glucose level above 1.26g/l (7mmol/l) associated with asthenia, weight loss, and anorexia. Cough and dyspnea, signs suggestive of tuberculosis, were found in 72.7% and 45.5% of patients, respectively. Most of the patients were in glycemic imbalance, but the severity of hyperglycemia did not seem to play a major role. Any hyperglycemia in a diabetic patient is a sign of unbalanced diabetes and is an additional factor in the depression of the patient's immunity, which could favor the occurrence of tuberculosis. This was the subject of this publication. The lungs were the most affected organs, which explains why pulmonary tuberculosis was the most common form of tuberculosis. This predominance of pulmonary tuberculosis over extrapulmonary tuberculosis in diabetic patients is consistent with the study by Diarra [19] and Traoré [24]. This suggests that diabetic patients develop more pulmonary tuberculosis. Kock's bacillus (BK) was found in only 27.3% of sputum. This rate is certainly due to the characteristics of the population studied, and would normally be higher because diabetes alters the immunity of patients, resulting in a higher mycobacterial load [17]. The pleurisies were exudative in 50% of the cases with a cellularity of less than 1000 elements per mm3, predominantly lymphocytic in the majority of cases (3 of the 4 cases found).

On the chest X-rays, the involvement of the lung parenchyma (isolated or associated with pleural involvement) was 81.8%. According to Eddaif, most of the studies conducted had not described any typical or specific radiographic pulmonary lesions in diabetics. Nevertheless, he states that excavation, bilateral involvement and base involvement have been described [25].

Diabetes was treated with insulin in all our patients according to other authors [15,16]. Pulmonary tuberculosis was treated with the ERHZ association as is the case for non-diabetic patients. This association of tuberculosis and diabetes requires good management, which is also based on the application of hygienic and dietary measures. The evolution was favorable in 72.7% of cases. However, the combination of tuberculosis and diabetes is an aggravating factor and tends to increase mortality. We reported a high death rate: 27.3% compared with 8% for Maalej [26] and 11.12% for Sidibé [24].

Conclusion

Tuberculosis is frequently associated with diabetes mainly in developing countries, 4.1% in our study, due to the increasing number of diabetics in the world. All types of diabetes are concerned. This association tends to be a real public health problem because of its clinical variability. It affects more women and is more frequent in the 45-59 age group. Tuberculosis in diabetic patients evolves favorably if diabetes is well controlled and if antituberculosis treatment is well followed. However, a significant mortality rate has been observed in our country, hence the importance of systematic screening for tuberculosis in all diabetic patients, and vice versa.

References

- Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. Rapport sur la lutte contre la tuberculose dans le monde 2016.

- https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/gtbr2019_pdf?ua=1

- Niang S, Thiam KH, Mbaye FBR, et al. Epidemiological, clinical and radiological profile of positive microscopy pulmonary tuberculosis (PMPT) at the Regional University Hospital Of Saint-Louis. Mal 2019; 34: 17-21.

- Oulahbal FB, Chaulet Conference on tuberculosis in Africa: epidemiology and control measures. Med Trop. 2004; 64: 224-228.

- Lot F, Pinget R, Cazein F, et al. Frequency and risk factors of the inaugural tuberculosis of AIDS in France. Bull Epidemiol 2009; 13: 289-293.

- Expert committed on the diagnostic and classification of diabetes mellitus. Report. Diabetes care. 1997; 20: 1183-1197.

- https//ww.who.int 2016

- Karuranga S, Malanda B, Saeedi P, et Atlas du diabète de la Fédération Internationale du diabète, 8 ème édition. Bruxelles. 2017; 6: 90.

- https://www.theunion.org.

- Restrepo BI, Camerlin JA, Rahbar MH, et al. Cross-sectional assessment reveals high prevalence of tuberculosis in newly diagnosed diabetes cases. 2011.

- Rugambwa S. Study on the diabetes-tuberculosis association in the medicine departments A, B, C, D at Point G (54cas). [Thesis]. Université de Bamako, Faculté de médecine. 1992;

- Aubertin Tuberculosis and diabetes. Journée Med Bordeaux. 1963; 4: 633 -646.

- Chabbou A, Kamel A, Jeguirim Prognosis of tuberculosis associated with diabetes. Med. Hygiène. 1982; 40: 1234-1241.

- Mugusi F, Suvai AB, Albertin KG. Increased of diabetes mellitos in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Tanzania. 1990; 71: 271-276.

- Frances L, Phil Tuberculosis in Ethiopian diabetes. Ethiop Med J. 1984; 22: 129 -133.

- Abbas N, Ayade S, Madache Pulmonary tuberculosis diabetes. Journ Alg Médecine. 1992; 4: 275-280.

- Morad S, Benjelloun H, Moubachi H, et Clinical, radiological and evolutionary profile of pulmonary tuberculosis in diabetics in the respiratory disease department. CHU Ibn Rochd de Casablanca. 2015; 32: A225.

- Balde NM, Camara A, Camara LM, et Tuberculosis and diabetes in Conakry Guinea: prevalence and clinical characteristics of the association. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006; 10: 1036-1040.

- Diarra B, Diallo A, Maiga Tuberculosis and diabetes in Bamako; Mali: Prevalence and epidemiological- clinical characteristics of the association. Revue malienne d’infectiologie et de microbiologie. 2014; 2: 24-26.

- Ibrahima Infectious complications of diabetes in Mali. [Thesis]. University of Bamako, Faculté de Médecine. 1986; 24.

- Rugambwa S. Study on the diabetes-tuberculosis association in the medicine departments A, B, C, D at Point G (54cas). [Thesis]. Université de Bamako, Faculté de Médecine. 1992;

- National Tuberculosis Control Program (PNLT) -MALI. Tuberculosis technical guide for health workers. 4ème éd. 2014; 144.

- Sidibé AT, Dembelé M, Diarra AS, et Pulmonary tuberculosis in diabetics in internal medicine G-spot hospital, Bamako-Mali. Mali Médical. 2005; 20: 25.

- Traore D, Sow DS, Sy D, et Tuberculosis in diabetic subjects in Bamako. Health Sci. Dis. 2020; 21: 15-20.

- Ilham Prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis in the diabetic population [Thesis], Faculty of medicine and pharmacy, Marrakech, Université Cadi Ayyad. 2018; 80.

- Maalej S, Belhouw N, Bourguiba M, et Pulmonary tuberculosis causes diabetes imbalance. Presse Med. 2009; 38: 20-24.