Recurrent Miscarriage and Consanguinity among Omani Women- A Cross Sectional Study

Author(s): Fatma Al Hoqani1, Wadha Al Ghafri2, Saneya El tayeb3, Yahya Al Farsi4 and Vaidyanathan Gowri5*

1 Resident Oman Medical Specialty Board.

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Sultan Qaboos University Hospital.

3 Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Muscat private Hospital.

4 Department of Family Medicine and community Health, Sultan Qaboos University

5 Department of Obstetrics& Gynecology, Sultan Qaboos University

*Correspondence:

Dr Vaidyanathan Gowri, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Muscat, Oman, Tel: +968-99416909, Fax: +968 24141162.

Received: 27 December 2020; Accepted: 18 Janaury 2021

Citation: Fatma Al Hoqani, Wadha Al Ghafri, Saneya El tayeb, et al. Recurrent Miscarriage and Consanguinity among Omani Women - A Cross Sectional Study. Gynecol Reprod Health. 2021; 5(1): 1-6.

Abstract

Objective: to determine the prevalence of explained and unexplained recurrent miscarriages (RM) and to find out if there is a significant relationship between recurrent miscarriages and consanguinity.

Methods: A cross sectional in which the cases group included all women with RM attending the outpatient clinic at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital from July 2006 to April 2012 and the controls group included women with no history of RM after matching them with cases for age (case to control ratio was 1:1). The main outcome measures were the prevalence of consanguinity in women with or without recurrent miscarriages.

Results: During study period a total of 290 women with RM were seen. Of which, 150 (51.7%) women had unexplained RM. Control group with no history of RM were 300 women. Consanguinity rate among cases (49.5%) %) was less than the controls (52.7 %%). Both first cousin and second cousin marriages were more common in the controls than the cases and it was not statistically significant (p value 0.476, chi squared test).

Conclusion: In this study we found that more than half of RM cases were unexplained and there was no significant association between RM and consanguinity.

Keywords

Introduction

Recurrent miscarriage (RM) is defined as spontaneous loss of three or more pregnancies consecutively prior to 20 weeks from the last menstrual period, before the fetus has reached viability [1]. It affects approximately 1% of women [2] and around 50% of these cases remain unexplained [3-5]. Many studies have demonstrated the detrimental effects of consanguinity on child health [6-10].

However, research findings regarding the risk of consanguineous marriage on RM are still controversial [11-18]. The practice of consanguineous marriage has been the culturally preferred form of marriage in most Arab and the Middle Eastern countries, including Oman [7]. The consanguineous marriage among Arab population is about 20-50% of overall marriages with first cousin marriage being the most common 25-30% [19].

Although there are many identified causes for RM, a large portion of RM are due to unexplained reasons. Therefore, further research is needed in order to discover these unexplained reasons, and with the mixed findings regarding consanguinity as a risk factor it is important for research to be conducted on consanguinity and RM to establish or eliminate it as a risk factor. The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of RM and to find out if there was a significant relationship between RM and consanguinity in a hospital setting.

Materials and Methods

7 women with two consecutive second trimester miscarriages were included. - Comment on that this was a cross sectional study of women attending outpatient clinic of gynecology department at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital (SQUH) from July 2006 to April 2012. Information was collected from patient's electronic medical records in the Hospital Information System (HIS) at SQUH. The cases were women with RM and the controls were 300 women who had no history of RM delivering in the same hospital (case to control ratio was 1:1). Both study and control groups were matched for age (± 1 year). The statistical software package SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) was used for all data analyses. Participants' socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics were described in quantitative terms using tables, drawing graphs, calculating some statistical parameters like mean and standard deviation. Chi-Square test was used to find out the association between different parameters, p value < 0.05 was considered significant. Bivariate Analysis was used to assess the association between the age and parity as risk factors and prevalence of unexplained RM. Chi-square test (χ2) and odds ratio (OR) was applied to find the significance of the association between unexplained RM and consanguinity. Moreover, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for odds ratio was calculated by using the binary logistic regressions. Adjustment for confounding factors was also used to eliminate the effects of age and parity as confounding factors on the relationship between RM and consanguinity. An adjusted OR with 95% CI that did not include 1.0 was considered significant.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee at Sultan Qaboos University (SQU), College of Medicine and Health sciences before the implementation of the study. This was not funded and extra data on etiology of RM is available with the first author of the manuscript.

Results

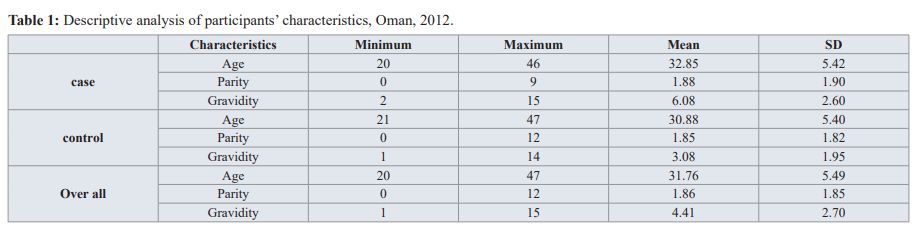

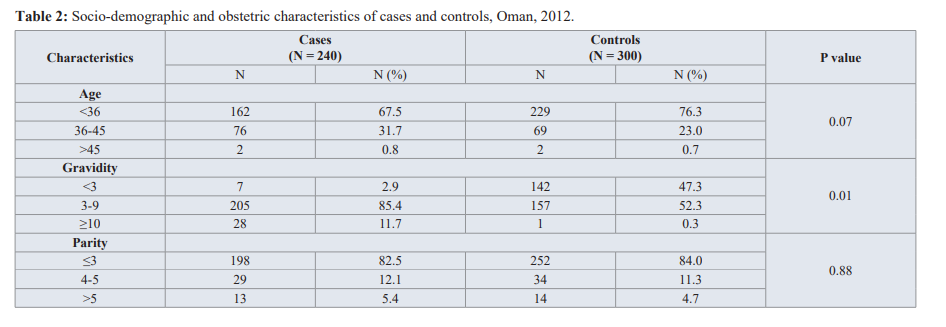

This study was conducted from July 2006 to April 2012. Throughout this period, there were 290 women with RM. Data on consanguinity was available for 240 women with RM (cases) and all the controls. The mean age of the participants was 31.76 ± 5.49 years. There was no significant difference in mean age between cases and controls (p=0.07. Distribution of age, gravidity and parity for cases and controls is shown in table 1.

The overall gravidity was 4.41 (SD 2.70). There was a significant difference in mean gravidity between cases and controls (p=0.01); mean gravidity of cases was 6.08 (SD 2.60) compared with 3.08 (SD 1.95) for controls (Table 1).

The overall mean parity was 1.86 (SD 1.85). The mean parity was almost equal in both groups; 1.88 (SD 1.90) for cases compared to 1.85 (SD 1.82) for controls (Table 1).

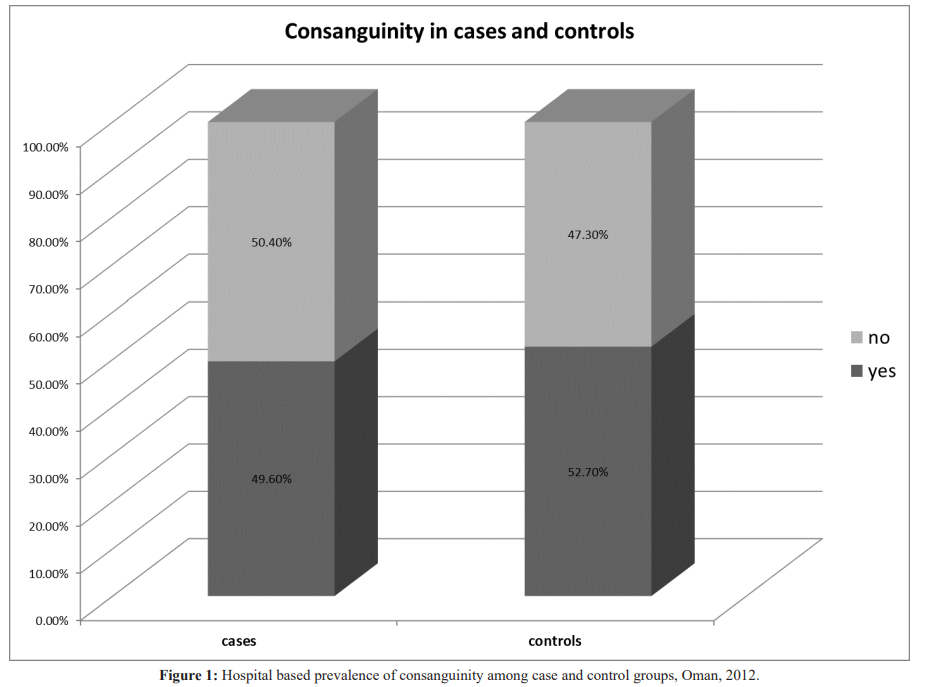

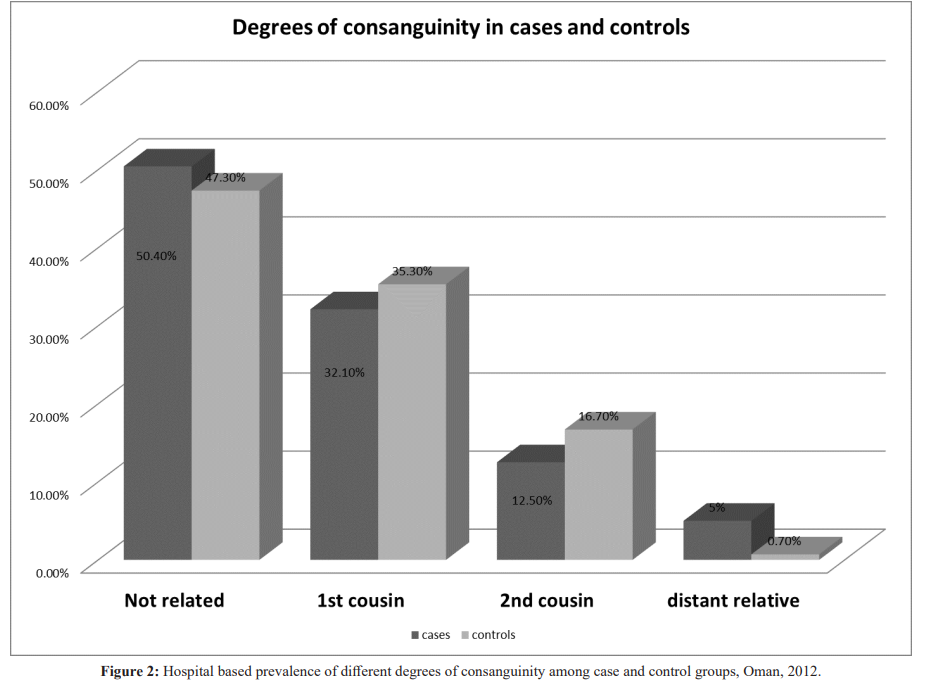

The overall consanguinity rate of the sample was 51.2%, 52.7% in the controls and 49.6 % of cases had consanguineous marriages (Figure 1). Among both groups first cousin marriage was the most common type of consanguineous marriage. 32.1% of the cases were married to their first cousin compared to 35.3% in the control group (Figure 2). The “p” value for consanguinity between cases and controls is 0.476 by chi squared test.

Discussion

RM continues to be an emotionally devastating problem for both physicians and patients. In this study we found that the prevalence of RM was. The mean age of the study group was 31.76 ± 5.49years. The age distribution of patients in the two groups (cases and controls) was comparable. In addition, there was no significant difference among the age subgroups (p=0.946); less than 36 years and 36 to 45 years (46.0% and 47.3% respectively). There was a high prevalence of consanguinity among cases and controls, especially first cousin marriages. There was no significant association between RM and consanguinity in this study.

This study is the first of its kind with matched controls for RM in the Sultanate of Oman. It is a cross sectional study with adequate number of controls included for each case RM. The main limitation in this study is that this data may not represent the whole Omani population because it was just taken from one hospital (SQUH), even though this hospital does receive referrals from all over the country. The retrospective nature of the study and the difficulty in making sure that some cases were really unexplained miscarriages are the other limitations.

Many studies have shown a strong association between reproductive wastage and demographic and socio-economic factors such as age and parity [6,20-23]. Advanced maternal age at conception has been recognized as a strong, independent risk factor for miscarriage, due to an increase in chromosomally abnormal conceptions [13,20]. The risk of miscarriage is directly related to maternal age at conception. After the age of 35 years, the risk of fetal loss increases sharply, rising from less than 15% among women aged less than 35 years to 75% at 45 years and older [20]. Women aged 40 years or more have poor chance of a successful pregnancy, with higher risks for miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, or stillbirth compared to women in their 30s [20].The finding that there was no statistically significant difference in the rate of miscarriages between the two study groups was probably due to matching that was done between cases and controls. Though a difference between the different age subgroups was expected but was not found.

As explained by Assaf et al. in their study about consanguinity and reproductive wastage in the Palestinian Territories, there are two possible explanations for the importance of parity and gravidity as risk factors for RM; First, parity is closely related to age, naturally older women have had more children than younger women, so the significance of parity could be due to inability to control for age. Second, the probability of experiencing a miscarriage is directly proportional to the number of pregnancies. The mean parity among both groups was equal to1.8, with no significant difference in the number of children between different sub-groups of parity. However, there was a significant difference in the mean number of gravidity between cases and controls (p=0.01); as they were 6.08 among cases and 3.08 among controls, with almost 12% of the cases having more than 10 pregnancies.

This study showed a high prevalence of consanguinity among both cases and controls with the highest percentage observed among first cousins. This is comparable to that reported in many studies from different Arab countries, including Oman [24,25]. However, this observation cannot be generalized, because the sample may not represent the whole Omani population.

The association of consanguinity with other reproductive health parameters, such as fertility and miscarriages, especially RM, is controversial. Consanguinity can have both negative and positive/neutral effects on reproductive health. The negative effects of consanguinity on reproduction include an increased risk for autosomal recessive diseases, congenital disorders, mental retardation, decrease in birth weight and postnatal mortality among the offspring of consanguineous parents compared to non-consanguineous parents who may be related to the action of deleterious recessive genes and multi-gene complexes inherited from a common ancestor [6-10]. Parallel to the huge body of literature detailing the negative effects of consanguinity on human health, there also exists a considerable amount of data that suggests that the practice of consanguinity is not the great evil that it is generally thought to be. Neutral or positive effects include a higher fertility rate according to some studies. Our finding that there was no significant association between RM and consanguinity is in agreement with that reported in some studies [11-14] but not others [6,7,13,17-19].

Strengths and Limitations of this study

- This is one of very few in a consanguineous population regarding miscarriages.

- The results are very relevant in counseling the couples.

- The limitation is its retrospective nature and the data is from a single center though it is a referral hospital.

Conclusion

The present study showed no significant association between RM and consanguinity.

References

- Waburton D, Strobino Recurrent spontaneous abortion. In: Bennet MJ. Edmond DK (eds). Spontaneous and Recurrent Abortion. Oxford: Blackwell. 1990; 109-129.

- Stirrat Recurrent miscarriage. Lancet. 1990; 336: 673- 675.

- Porter T, Scott Evidence-based care of recurrent miscarriage. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005; 19: 85-101.

- Li T, Makris M, Tomsu M, et al. Recurrent miscarriage: Etiology, management and prognosis. Human Reproduction Update. 2002; 8: 463-481.

- Clifford K, Rai R, Regan L. Future pregnancy outcome in unexplained recurrent first trimester miscarriage. Human Reproduction. 1997; 12: 387-389.

- Assaf Sh, Khawaja M, DeJong J, et al. Consanguinity and reproductive wastage in the Palestinian Territories. Pediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2009; 23: 107-115.

- Islam MM. The practice of consanguineous marriage in Oman: prevalence, trends and determinants. J. Biosoc Sci. 2012; 1-24.

- Rajab A, Patton A study of consanguinity in the Sultanate of Oman. Ann Hum Biol. 2000; 27: 321-326.

- Bener A, Hussain R. consanguineous unions and child health in the state of Qatar. Pediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2006; 20: 372-378.

- Hamamy H. Consanguineous marriages: Preconception consultation in primary health care settings. J Community Genet. 2012; 3: 185-192.

- Banerjee S, Roy T. Parental consanguinity and offspring mortality: the search for possible linkage in the Indian Asia-Pacific Population Journal. 2002; 17: 17-35.

- Hussain R. The role of consanguinity and inbreeding as a determinant of spontaneous abortion in Karachi, Pakistan. Annals of Human Genetics. 1998; 62: 147-157.

- Mokhtar MM, Abdel-Fattah MM. Consanguinity and advanced maternal age as risk factors for reproductive losses in Alexandria, Egypt. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2001; 17: 559-565.

- Yassin K. Incidence and socioeconomic determinates of abortion in rural Upper Public Health. 2000; 114: 269- 272.

- Abdulrazzaq Y, Bener A, AL-Gazali L, et al. A study of possible deleterious effects of consanguinity. Clin Genet. 1997; 51: 167-173.

- Gowri V, Udayakumar A, Bsiso W, et al. Recurrent early pregnancy loss and consanguinity in Omani couples. Acta Obstetricia ET Gynecological 2011; 90: 1167- 1169.

- Khlat M. Consanguineous marriage and reproduction in Beirut, American Journal of Human Genetics. 1988; 43: 188-196.

- Saad FA, Jauniaux E. Recurrent pregnancy loss early and consanguinity. Reproductive Biomedicine. 2002; 5: 167-170.

- Tadmouri G, Nair P, Obeid T, et al. Consanguinity and reproductive health among Reproductive Health. 2009; 6: 17.

- Rai R, Reagan Recurrent miscarriage. Lancet. 2006; 368: 601-611.

- Stephenson, Awartani KA, Robinson Cytogenetic analysis of miscarriages from couples with recurrent miscarriage: a case- control study. Hum Reprod. 2002; 17: 446-451.

- Caetano M, Couto E, Junior R, et al. Gestational prognostic factors in women with recurrent spontaneous abortion. São Paulo Medical Journal. 2006; 124: 181-185.

- Macklon N, Geraedts J, Fauser B. Conception to ongoing pregnancy: the ‘black box’ of early pregnancy loss. Human Reproduction. 2002; 8: 333-343.

- Sulaiman AJ, Al-Riyami A, Farid S. Oman Family Health Survey 1995. Final Report. Ministry of Health, Muscat.

- El-Mouzan MI, Al-Salloum AA, Al-Herbish AS, et al. Regional variations in the prevalence of consanguinity in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal. 2007; 28: 1881-1884.